Spoilers for One Battle After Another ahead.

At the beginning of One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson flirts with a defeatism, seemingly rationalised via biology: the inability to escape the sexual drives which transcend all ideology. Amidst the militantly organised liberation of a migrant detention centre by rebel outfit The French 75, Perfidia Beverly Hills (played by Teyana Taylor) confronts head of the detention operation Colonel Steven Lockjaw (played by Sean Penn). Polar opposites in the heat of battle, there is still an undeniable force between them: Lockjaw’s feverish sexual obsession with her, and Perfidia’s own desire to control him through this obsession – one which she enjoys, but can casually play off given the circumstances. This play of sexual power presents an initial dilemma – what does the right hold that the left doesn’t, and vice versa? What is to be made of the radical if the conservative is so alluring? Are we thus faced with, to quote Jacques Derrida, a vis a vis? Is there a compromise?

The rest of the film, however, is not content with this. Indeed, their “union” reflects the core ideological conflict that underpins the film – that is to say, we live in the aftermath of the vis a vis. This is a fake co-existence that presents itself as truth and freedom, but has only violently exacerbated the forces of the right; stagnating the present in a turmoil where the libidinal frustrations of then not only resonate now, but have become far cruder; far more unsatisfied; restless; esoteric; fascistic. Our mistake is in thinking that the libido instils a necessary compromise. Instead, the libido insists that there is a field that the left – the ‘radical’, the ‘revolutionary’ – has yet to fully appreciate or understand. Perfidia was a rat, and the vibrancy of her rhetoric conflicted with an incomplete (albeit determined) desire for radical action, but she was not wrong to lust. Libido is not a trap which will always halt radical action. It is, however, rooted in the anxieties and dissonances which inform our spirits. Her charged intimacies with Lockjaw merely manifest her own structural desires; which transcend ideology in so far as she wishes to be rid of the ideological fight – for herself, more than for her friends and family. This is why she flees the home that Lockjaw helped her secure in witness protection, as the reality of her libidinal limits have become all too apparent. She must run, for staying will never grant her rest. This is decidedly not Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland; where the flaccid utopianism of 60s hippiedom has been replaced by the CIA philosopher-kings of Brock Vond. In Anderson’s world, the cultural rot has already set in. Everything is the same as it was 16 years before, only with different shades and patinas. Its racisms are grizzled but with a post-familial legacy far beyond that of its radical counterpart (a brilliant cameo from veteran Kevin Tighe epitomises this). There is nothing of Mark Fisher’s acid communism, only an unsolved libidinal maze.

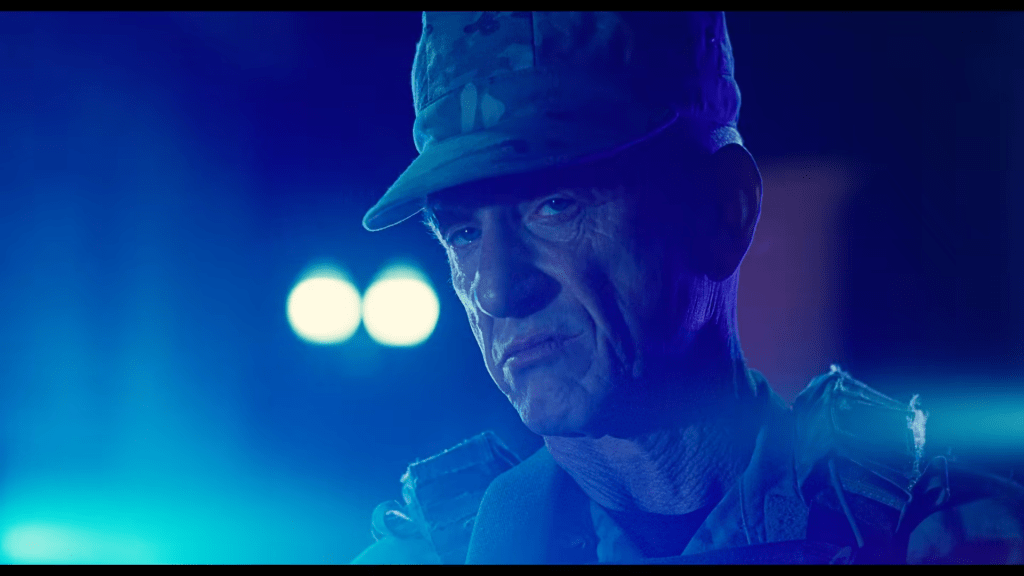

In this vein, though the central narrative is between Bob Ferguson (aka – Rocketman, or ‘Ghetto’ Pat Colhoun) and his daughter Willa (aka – Charlene Calhoun), it is Steven Lockjaw who becomes the de facto main character. Lockjaw is a man whose military life has long been the manifestation of a repressed libido, unable to come to terms with who he is as a white heterosexual man in a world that despite his best efforts is always moving beyond him. He must find security in the hegemony, so much so that he strives to join the Christmas Adventurers Club: an elite cult of white supremacists whose connections to the abstract avenues of capital – military, industrial, state, local, wherever and however – are what Lockjaw strives for. He wants to be like these guys. Gilleted and wanting for nothing, sleek in their WASP-ish charms, and unencumbered by fragilities. But Steven Lockjaw is a fragile man. His militant stride is both affected and naturalised. Whilst not short, he is shorter than the men around him, and thus attempts to command a mannekinesque authority. Anderson gets “on his level”, often shooting from low angles, but such pretences rarely grant him the authority he desires. He has a gnarled face, constant mouth ticks, overly-militant expressions, and uses spit as hair gel for an atrocious hairstyle that reads as a naive alt-right undercut. He reads as a man who has spent so many hours staring at his peculiarities in the mirror that he has forgotten about the very spirit which that vessel carries. His hatred for non-white folk has all to do with wanting more for himself; for securing a place that the military has been unable to entirely grant him. His attraction to Perfidia – a black woman whose relationship to her race is far more radical and open than Lockjaw’s own relationship to his whiteness – is a contradiction. Yet more significantly, this element of his attraction becomes violently intensified as he cannot view his own libido beyond the structures of race and capital that he has devoted himself to in the pursuit of a calmness to his restless inner spirit.

It is the strive for him to eliminate all traces of his association with the Other that thrusts the film forward, reigniting a momentary revolution for which he is the villain to overcome. Of course, destiny has another fate for him. The revolution never gets close to harming him really. Even when Bob has him in the sights of his sniper, he misses and Lockjaw keeps on walking as if nothing has happened. He gets close to death when, after finally kidnapping Willa and leaving her fate in the hands of a white supremacist sect of the military, a hitman hired by the Christmas Adventurers – after discovering his relationship to Perfidia and the existence of their child, Charlene/Willa – shotguns him in the face, causing him to career his car off the road. He somehow survives, striding back towards us with a face bloodied and mangled. After the dust has settled and his face has healed into a permanent scar, he returns to the Christmas Adventurers, ignorant of their initial plan. Thinking that he has finally made it into their echelons, he is guided to an office where he is locked in, quietly gassed to death, and then quickly cremated. A bigger and more efficient power works beyond him, despite his apparent control over military might and a state apparatus that is seemingly at his command and willing to divorce violent personal action from violent political action. To reference another DiCaprio film, he is this story’s Ernest Burkhart – a man too ignorant and blinded by desire to realise his role in the grander scheme of capitalist oppression but likewise a repugnant pawn who ends up a squirming figurehead of the libidinal hegemony. The title – One Battle After Another – thus rears its head again: there is always more work to be done.

Put simply, Lockjaw is a caricature of the fascist libido; or at least one strain of it. He is a caricature in this sense that in the will to conceive of sexual politics along such masculinist conservative lines – a casualised sadomasochism devoid of consent, mutuality, and tenderness – the contradictions bloom into the esoteric and the abstract; the frightening tentacular paradoxes which only grow stronger and more numerous the more you resist. When we speak of genres being bodily – to hint at Linda Williams’ seminal ‘Film Bodies’ – the narrative’s evolution into suspense action drama seem almost to be the translation of Lockjaw’s lack of fulfillment; pushed onto everyone around him and into cinematic spacetime. Bob and Willa Ferguson’s world ripples and clunks at Lockjaw’s repressions now that he has announced himself on the stage of the uber-fascists themselves, with no hope of turning back other than the death which ultimately befalls him. Perhaps this is why Paul Thomas Anderson sacrifices some of the stronger compositional tendencies of works like Inherent Vice or The Master. Instead, he opts for something closer to an affective continuity or montage: a stronger sense of images in flow and transition, as meaning arriving from something less causal and more spasmodic and tortured; desperate for a climax.

Leave a reply to Heather Cancel reply